Kubernetes Networking

Introduction

Kubernetes networking is a fundamental aspect of cloud-native systems, enabling seamless communication between pods, services, and external resources. This post, extracted from my postgraduate research Performance Analysis of Zero Trust in Cloud Native Systems, delves into the core principles and mechanisms that underpin Kubernetes networking. By understanding these concepts, you can effectively design and manage robust, scalable, and secure network architectures within Kubernetes environments.

Kubernetes Networking Model

Kubernetes networking model is based on a few fundamentals rules, where pods should be able to communicate with other pods without Network Address Translation (NAT), programs running on a node should communicate with any pod on the same node without using NAT, each pod has an Internet Protocol (IP) address that can be reached by any other pod in the cluster.[1] This model is referred to as a “flat networking model” and greatly supports microservices architectures by facilitating the communications between containers.

Figure 1: Kubernetes Components

Figure 1: Kubernetes Components

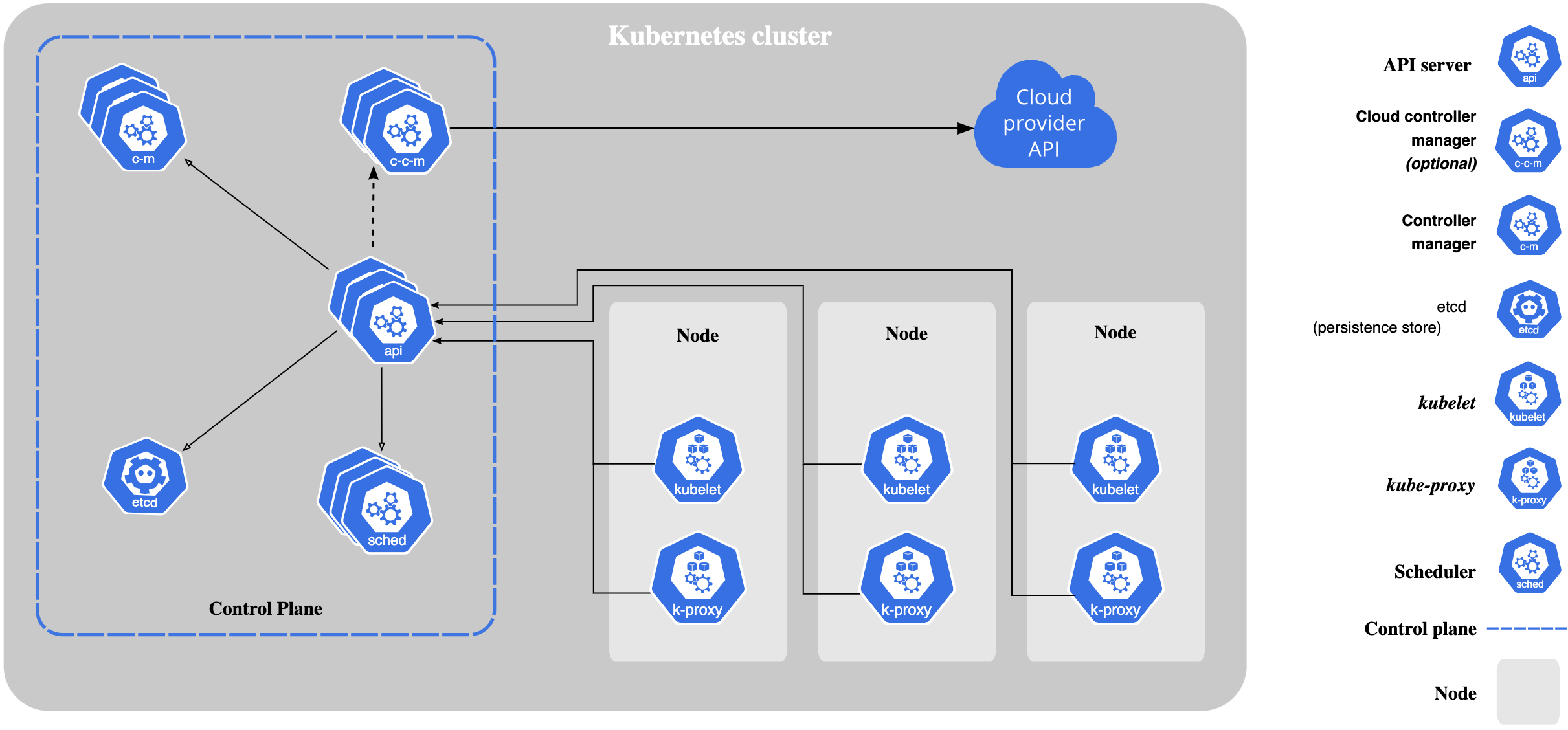

When creating a managed Kubernetes cluster in a PCP, nodes within the cluster get assigned an IP address part of the Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) network, this is the node’s connection to the rest of the cluster. This IP allows connectivity from control components like kube-proxy and kubelet to the Kubernetes API server, as described in figure Figure 1. Pods running on each node get an IP from the node IP address pool is a Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) range specifically assigned to pods and part of the cluster’s configuration. The pod IP address is shared by containers part of the pod and provide communication with other pods in the cluster.[2][3]

Figure 2: Linux network namespaces and pods

Figure 2: Linux network namespaces and pods

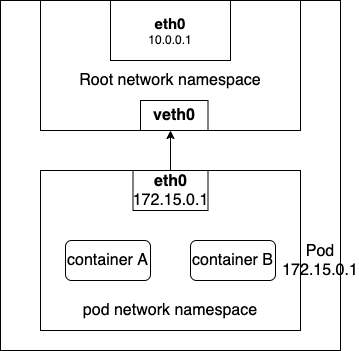

CNI, Pods and Services

When a pod is created, and the pod gets assigned to a node by the Kubernetes scheduler, the pod gets its own Linux network namespace on the node, the container network interface (CNI) assigns an IP address to the pod and attaches the pod to the container network, network packets can then flow to and from the pod. If multiple containers are part of the same pod, all containers will be part of the same network namespace. Linux has the ability to create several virtual device types and veth is one of them. veth are virtual ethernet devices which are created in pairs and are typically used to connect network namespaces. Figure 2 illustrates the final state of a pod creation, where the CNI creates a network namespace and assign an IP for the pod and then attaches the pod to the host network by creating a veth pair.

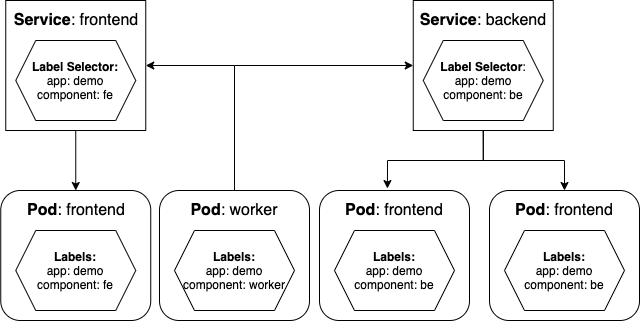

Pods are ephemeral by nature, since Kubernetes regularly destroys and recreates them when pods configuration is updated, node pools are upgraded or nodes become unavailable. As a consequence, the IP address assigned to a pod is not reliable. Kubernetes uses another abstraction to provide a stable IP address and ports: services. Each Service has an IP address, called the ClusterIP, which is assigned from the cluster’s VPC network. This IP address is stable and does not change during the lifetime of the service. Services use pod labels to group multiple pods in a logical unit and act as a load balancer for the set of pods that match a given label, this is done using a label selector in the service configuration.[2][3][1]

Figure 3 describes how services and pods communicate using labels and labels selectors. The service front-end provides access and load balancing for pod front-end since the pod matches all labels defined in front-end label selector. Similarly, the back-end service load balances the two back-end pods that matches all labels of back-end service. If a pod does not match all labels of any service, for example the worker pod in Figure 3 can still communicate to all services in the cluster, but it is not reachable via any services.

Figure 3: Kubernetes Services and labels

Figure 3: Kubernetes Services and labels

kube-proxy

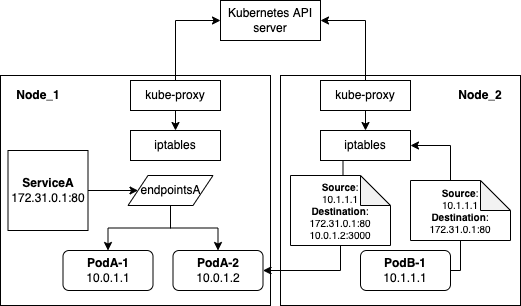

The default networking configuration in Kubernetes avails of kube-proxy abstraction which leverages iptables. Iptables is a user space interface to set up, maintain and inspect the tables of IP packet filter (Netfilter) rules in the Linux kernel.[4] The role of kube-proxy is to assure clients can connect to services defined via Kubernetes API so that connection to the service IP and port is redirected to a backing pod. If more than one pod is backing a service, the kube-proxy performs load balancing across those pods.[3] A kube-proxy runs on each node as a static pod and is not an actual proxy, its function is to update iptables rules to redirect network packets to pods.[2]

Figure 4: Pod to pod networking

Figure 4: Pod to pod networking

The name kube-proxy was given based on the original, less performant implementation, where the kube-proxy was acting as a proxy intercepting connection destined to a service IP and configuring iptables rules to redirect the connections to a proxy server \cite{kubernetes_in_action}.

Figure 4 describes the role of kube-proxy and how a network packet is sent from PodB-1 to the virtual IP 172.31.0.1 of ServiceA. The kube-proxy watches for changes to services and endpoints via the Kubernetes API server and updates iptables rules accordingly. When the packet is sent from PodB-1, the node kernel checks iptables rules and one of the rules says the virtual IP needs to be replaced with the IP and port of a randomly selected pod, in Figure 4 the randomly selected pod is PodA-2 which is a pod matching all labels selectors of ServiceA, as previously described in Figure 3.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Kubernetes networking is a critical component for the efficient operation of cloud-native applications. By adhering to the fundamental principles of the Kubernetes networking model, such as the flat networking model and the use of IP addresses for pod communication, organizations can achieve seamless and scalable communication within their clusters. This model not only simplifies the network configuration but also enhances the performance and reliability of microservices architectures.

Furthermore, understanding the intricacies of Kubernetes networking allows for better design and management of network policies, ensuring secure and robust communication channels. As cloud-native systems continue to evolve, mastering Kubernetes networking will be essential for leveraging the full potential of container orchestration and maintaining high standards of security and performance in dynamic environments.

References

1 - Kubernetes official website

2 - Google Kubernetes Engine: Network overview

[3] Kubernetes in Action, Marko Luksa, 2018

[4] Assessing Container Network Interface Plugins: Functionality, Performance, and Scalability, Qi, Shixiong and Kulkarni, Sameer G. and Ramakrishnan, K. K., IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, 2021, DOI:10.1109/TNSM.2020.3047545